17 year-old Anna Lovat on the endangered world of 20,000 species

February 9, 2024

‘Save the bees!’ Of course, but which bees?

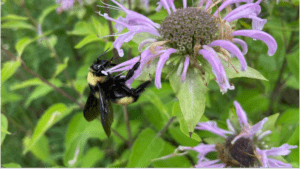

Picture for a moment, a bee. Most likely, you’re visualizing a honey bee.

Yet there are around 20,000 known bee species in the world, and honey bees make up just a tiny fraction of that.

Although our eyes are trained to recognize yellow and black stripes, bee species range wildly in color and size; from metallic green to beige and from under two millimetres to over four times the size of honey bees.

Much attention and concern has swarmed around honey bees socially, as attention is being brought to the global decreases in honey bee hives, and the threat this poses to agricultural crop yield.

Also written by Anna:

‘A German study conducted in nature reserves over a period of 27 years found a decline of 75% in insect biomass 26 — a trend that is seen reflected across the globe’

News coverage has popped up left and right, linking this decline in honey bees to issues such as colony collapse disorder (CCD) and deformed wing virus (DWV). But, contrary to public perception and common media portrayal, it isn’t just the honey bees at risk.

The insects that are most at risk of extinction receive negligible amounts of press and public attention. Conversations around insect decline are often simplified into the decline of pollinators, and from there, the risks that honey bees face.

This is misleading- and sets a dangerous precedent for the ways we interact with insects.

From cuckoos to sweat bees

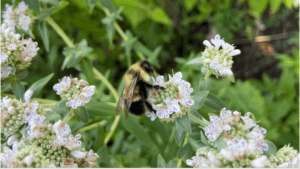

The vast majority of bees are solitary, which means they do not interact with humans or build the hives that are traditionally associated with bees- nor do they produce honey.

Instead, these bees live and work on their own, laying eggs in small burrows they create, eating pollen and nectar, as well as providing their offspring with limited parental care.

Very few of these bees sting, and they live around us, unnoticed and unappreciated- and yet, are responsible for the majority of pollination for gardens, ornamental plants and wildflowers around us.

Although these solitary bees (also often referred to as ‘wild bees’) range greatly in appearance, lifestyle, and habitat, each (non-parasitic) bee has scopa-tiny, branched hairs designed for maximum pollen collection- on their hind legs or the underside of their abdomen. This, particularly in mason and leafcutter bees, allows for greater rates of pollination.

Mason bees pollinate 95% of the plants they visit, as compared to a honey bee’s 5%.

Leafcutter bees cut small, near-perfect circles out of leaves for use in the construction of their homes. Cuckoo bees are known for their kleptoparasitic life cycle, sneaking into the burrows of other bees, and laying their brood in the nests. Halictidae, or sweat bees, are the second largest family of bees and can be found searching for precipitation along with nectar.

Around 20% to 45% of wild bees are specialists, a term which signifies that the bee only uses pollen from a specific genus of plants. These bees aren’t talked about and are facing rapid rates of decline.

There are many reasons to be worried about insect health- particularly the loss we are seeing in pollinating species. However, this sudden craze in keeping honey bee hives- especially as a move by corporations to appear more eco-friendly, actually puts many bees at risk.

With the rise in popularity of the “Save The Bees” movement, more and more attention has been directed towards the protection and preservation of honey bees – with little attention or funding directed towards the bees who exist outside of the public eye.

Honey bees are recognizable and known for their pollination prowess, a combination that has made corporations and business a profitable trend for marketing.1

Why do we need honey bees?

The collective term ‘Honey bees’, or Apis Linnaeus, is composed of eight species out of the 20,000 named bee species known to science. First endemic to Afro-eurasia, honey bees colonies were brought to North America during European colonization and the trans-atlantic slave trade, quickly spreading across the continent as a source of pollination.

Honey bees have been domesticated for over 7000 years, and can be seen flying throughout a majority of the world’s countries.

This is not to say we don’t need honey bees- in fact, the exact opposite is true. Honey bees are absolutely essential in agriculture for their roles in pollination services.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) found they “pollinate $15 billion worth of crops in the United States each year, including more than 130 types of fruits, nuts, and vegetables.”

That statistic is similar to the $22 billion reported by the European commission, which cites both honey, bumble and native bees as the source for “pollination for over 80% of crops and wild plants in Europe.”

Honey bees play an integral role in our agriculture systems, and that’s not where the harm is stemming from. Honey bees should not be viewed or treated as the enemy. Rather, our current perception acquits all bees to honey bees – a belief that is seen frequently in media, such as the ever infamous Bee Movie.

To work against the decline of pollinators and the simplification of bee species, it may be best to view and treat honey bees as livestock.

The trends that determine conservation

Honey bee hives are rented and shipped throughout the world, being imported and exported everywhere from California’s almond groves to states in the European Union. For years, we have continued to see a surge in the desire to keep honeybees. What caused this sudden spike in beekeeping? Trends!

Alternative milk sources have been rising in popularity over the past ten years, with almond milk being a popular competitor. California is the center of the world’s almond production, growing 80% of the world’s almond supply, and honey bee’s are the main source of almond pollination.

Thus, honey bee hives all across the United States are rented and shipped out to farmers in California, going back at the end of the growing season.

Read also:

On a wider scale, corporations and businesses across the world have jumped at the chance to install honey bee hives, a move that is considerably more harmful than helpful.

For one, this is ‘greenwashing’ – an action taken by large corporations to appear more ‘eco-friendly’ and ‘environmentally conscious,’ profiting off of this appearance rather than actually taking action.

In 2016, a surge of media and public attention was brought to the decline of honeybees. Cheerios mascot, “Buzz the Bee” disappeared from boxes, in order to call attention to colony collapse disorder, or CCD – when the majority of worker honey bees suddenly vanish, leaving behind stores of food, young, and a productive queen.

This, combined with the growing belief that introducing more and more honeybees to various environments is “helping” the bees- is a deadly one.

While a well meaning gesture, it does not address the root issues of pollinator decline, nor are many prepared for the work that comes with keeping a hive.

Competition for food between native and honey bees is common, especially within urban environments, where there is often not enough food to sustain native bees, without the inclusion of honey bees.

This results in wild bee species being forced out of their habitat, which has been documented in various studies across the world, ranging from Africa to Australia.

To address this, the responses to people interested in beekeeping have evolved. Elise Bernstein, of the University of Minnesota’s Bee Lab spoke about her lab’s response to people interested in keeping honeybee hives.

“There was a time before I was working with the Bee lab that if somebody said, I want to become a beekeeper, it was like, okay, here you go. Whereas now when somebody is like, I want to be a beekeeper, our response is more like, why? If you’re interested in helping bees, here’s all the different things you can do.”

How can native bees be helped?

To create hospitable environments for solitary bees, we must consider the world they are facing. Urbanization and big cities lead to a lack of available resources, both for food and nesting. The actions we can take are astonishingly simple – create better habitats for them.

Native bees benefit from native plants that bloom throughout the spring to fall. Plenty of free resources, like the Pollinator Partnership’s planting guide allows for you to find the best indigenous plants for your home.

An additional simple step is letting dandelions grow in your yard. While we might see them as weeds, dandelions are one of the first plants to flower in the spring, providing vital nutrients and pollen for solitary bees awakening after a long winter.

To provide nesting spaces for solitary bees- don’t clean up your garden! Bernstein notes that “in your pollinator garden, cutting back stems to leave long hollow cavities for bees to nest in, and not cutting everything down to the ground at the end of the season, leaving those available for bees..makes an attractive setting.”

Bee homes have also become a popular option for supporting native bees for those without gardens. Often described as the insect equivalent of a bird house. Also referred to as nesting blocks and bee hotels, these structures are a place for solitary bees to shelter and lay their young.

Providing spaces for wild bees to prosper is easy to do, but there are key steps involved to maintain a healthy environment in bee hotels. Thyra McKelvie, of “Rent Mason Bees” spoke with me on the importance of safe habitats- and how some commercially sold bee homes can be unfit for solitary bees.

As bee hotels are frequently sold without instructions, assumptions grow that one can leave a bee hotel outside throughout the year, without taking additional steps.

However, nesting material for bee homes should be easily able to open for annual cleaning. Sturdy materials like bamboo can become a habitat for predators of bees over time.

As mason bees live only six to eight weeks, their nesting material should be removed at the end of spring and stored safely over summer. In the fall, the nesting material should be opened and cocoons extracted and cleaned. Old material must be sterilized to reuse, as disease and parasites can quickly spread to the next generation of nesting bees.

McKelvie emphasized the often unknown effects of bee homes that are not appropriately tended to. “If not cared for properly, these homes can become a predator habitat..over time, they could annihilate your mason bee population.”

For those who are prepared to look after a bee home, Professor Joel Gardner, of the University of Minnesota’s bee lab, authored a do-it-yourself guide for those who wish to make their own.

But as we now know, saving the bees is nuanced- and to protect our native bee species, we need this knowledge to spread. There’s no one step that will suddenly revitalize bee populations- but there are actions we can take to support our local insect species.

By taking steps to educate ourselves about the many species and intricacies of bees, and sharing that information with those around us, we are spreading the knowledge that there’s lots more out there than just honey bees!

At one point in time, the actions we saw as most helpful to bees was to simply bring more honeybees into the environment.

There is space for honeybees and wild bees to coexist together, but due to a general lack of knowledge, this simply isn’t happening. It is also a disservice to write and cast honey bees as “bad” and wild bees as “good.”

When we only recognize honeybees and their importance in discussions about pollination and pollinator loss, we are enforcing the decline of native bee species that are integral to ecosystems, and how we live our lives.