17 year-old Mykyta Yaremenko explains the failure of peace process in Kosovo

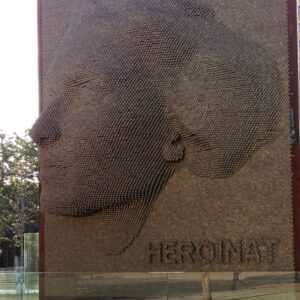

The 'Heroinat' (Heroines) monument in Pristina, Kosovo, is dedicated to women victims of sexual violence during the Kosovo War, of which the vast majority were Albanian women.

October 27, 2023

Kosovo War – understanding the unresolved conflict

In 2023 the situation in the Balkans, specifically on the Serbia-Kosovo border, started escalating. On September 24, heavily armed Serbian militants ambushed the Kosovo police in a village dominated by Serbians, which resulted in the death of a Kosovan officer.

This incident shed light on the conflict that tore the Balkans apart at the end of the 20th century. It was the last major conflict in Europe before Russia attacked Ukraine in 2014.

Currently, the conflict that was supposed to be resolved decades ago is making headlines in world news again, with the media asking ‘Are Kosovo and Serbia on the brink of war?’

The conflict is still present in the public debate, with politicians, like the Russian president Vladimir Putin continuing to mention the NATO bombings of Belgrade in their arguments, highlighting the importance of understanding the origins of this conflict.

What was the starting point of clashes in Kosovo?

When the Soviet Union was about to crumble and countries within Moscow’s sphere of influence regained independence, in 1989, Slobodan Milošević became the president of Serbia.

He believed that Serbians were humiliated by losing control over the territory of Kosovo in 1974. Likewise, he believed the Yugoslavian Constitution (1974), which aimed to provide stability by forming a Yugoslavia with six equal republics, disabled Serbia from asserting itself as a nation-state.

He wanted to amend the Serbian constitution in such a way that would restore Serbian national identity.

The constitutional amendments proposed in 1989 indicate this process of nationalisation and centralisation inside Serbia. Educational economic policies were to be coordinated with Serbia, provincial autonomy was reduced, and overall Serbia’s laws overruled all other laws inside Serbia.

The amendments undermined provinces’ autonomy, such as Kosovo’s. Kosovo’s officials were deprived of implementing policies and the local police force was shortened in its personnel and weaponry. Most importantly, they were unable to oppose the changes issued in Belgrade.

But, for this process of centralisation to be implemented, a vote had to take place.

While the voting process did take place in Kosovo’s Assembly, dozens of regulations were violated. For example, the Assembly’s inability to hold a voting process during a state of emergency, which was declared at this time in the Kosovo Autonomy Region. The major protests and riots that took place throughout the voting process gave way for Serbian officials to hold the province under martial law, even months after the vote took place.

The final spark that set off bloody wars all over Yugoslavia, was arguably Milošević’s Gazimestan speech. In it, Milošević highlighted: “through the play of history and life, it seems as if Serbia has, precisely in this year, in 1989, regained its state and its dignity and thus has celebrated an event of the distant past which has a great historical and symbolic significance for its future.”

The speech emphasised that the constitutional changes were going to bring back the deserved power and glory to Serbia, which suffered greatly in the past. This rise of nationalism led Serbians living in the country, as well as other republics in Yugoslavia to consolidate their power and restore their glory by force.

Ultimately, weakening the autonomy of regions, such as Kosovo.

NATO intervention and why is this a discourse topic?

Read more:

‘Twenty years after the start of NATO’s air strikes to force Slobodan Milosevic’s troops to withdraw from Kosovo, reporters who covered the bombing campaign recall the 78 days of violence, terror and destruction that changed the course of Yugoslavia’s history.’

Fighting had lasted for a year with no end in sight. Human rights violations and war crimes were committed by both the KLA and the Yugoslavian army together with the Serbian police.

While the UN Security Council did not pass any resolutions that allowed any intervention, NATO proceeded with air raids in attempts to secure control over the ground.

After 78 days of constant bombing of infrastructure in the Serbia and Kosovo region, forces asked for a ceasefire.

After the Balkan countries suffered almost 30,000 bombs, resulting in civil casualties and destroyed infrastructure, forces of the KLA and the Yugoslavian army started working on a peace treaty. On that same day, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1244 by a 14-0 vote, with one member absent.

What peace deal was established?

While Kosovo was not recognised as a state during the peace talks, the rule over economic policies, army and governing were executed by several organisations protecting their interests.

While NATO led the Kosovo army creating an international peacekeeping force – the Kosovo Force (KFOR), the main economic support to the Kosovo people was provided by the European Union.

The Resolution ordered the demilitarisation of the KLA and the withdrawal of the Yugoslavian army from the region. The resolution also established that the people of Kosovo suffered dramatic human rights violations committed by Serbian officials, and therefore cannot be ruled by them any longer.

What human rights violations occurred during the conflict?

Human rights violations were committed by the Serbian army and police, resulting in around 250,000 Albanians escaping from an attempt at ethnic cleansing. However, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) was also responsible for violations.

KLA was set up by Albanians living in Kosovo, who believed in the supremacy of pure ethnic Albanians. This resulted in almost 200,000 Serbians fleeing their homes, witnessing their churches and schools burned to the ground.

After the war ended, several cases were opened against human rights violations in Kosovo – of those several were viewed by the International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

These trials resulted in 5 out of 8 Serbs being prosecuted and eventually sentenced, and 6 Albanians, including former KLA commanders – Ramush Haradinaj and Fatmir Limaj – being acquitted. The Tribunal was closed in 2017 but still provokes debates over unexamined cases.