17 year-old Ayanna Rohil explains the significance of a pioneering transplant operation in the US

March 21, 2024. World’s first pig kidney transplant performed in Massachusetts General Hospital.

August 29, 2024

How the world’s first pig-kidney transplant operation could save lives

Doctors in Massachusetts have changed the face of medicine, after carrying out the world’s first kidney transplant operation using an organ from a pig in March.

Although the patient died two months after the operation, this transplant marks a milestone achievement, opening up the possibility of saving millions of other patients with the use of genetically modified animal organs.

The role of the kidneys is to filter out waste and excess fluids from the body, through the creation of urine. Patients can lose their ability to carry out this function from myriad causes including chronic kidney disease (CKD), high blood pressure, diabetes and cancer.

If this occurs, patients must go on dialysis, a procedure that replicates the filtering role of the kidney via passing blood through an external machine. This can typically only be performed on a short-term basis, while the patient waits for the long-term solution: a kidney transplant.

Traditional kidney transplants

A kidney transplant is a surgical procedure that places a donated kidney, taken from a deceased individual, relative, or any willing living donor, into the body of a patient whose kidneys are no longer functioning.

In 2022, more than 25,000 kidney transplants were performed in the United States, which marked the highest number of transplants in the world. Despite this figure, transplants are still extremely unsustainable – many more people need transplants than there are available organs.

At the end of 2023, 88,000 patients in the US were waiting for a kidney transplant. Currently, the American Kidney Fund reports that there are 92,000 (87%) people waiting for a kidney.

Suffering patients might end up waiting years to receive a kidney, by which point the transplant might not be in their best interests anyway; the risks of a lengthy surgical procedure under general anaesthesia could be too great in the patient’s current health.

On top of this, the donated kidney must meet a wide range of demands for the patient (blood type, tissue group, health of patient and donor) making the process even more lengthy to undergo transplant tests. Eventually, many patients end up unable to find proper treatment, risking death.

Mr Slayman’s journey

It is for this reason that the recent successful transplant of a pig kidney into a human patient, also known as xenotransplantation, has made headlines.

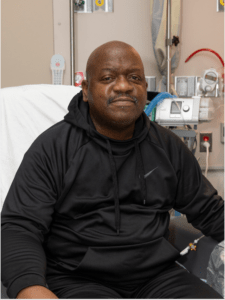

Richard Slayman, the first patient who received a genetically modified pig kidney transplant.

The procedure, carried out at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) by Harvard Medical School physician-scientists, transplanted a genetically modified pig kidney into 62 year-old patient Richard Slayman.

Mr Slayman had received a previous kidney transplant five years earlier, but his body ended up rejecting the kidney (meaning the cells in the body recognized it as an outside addition, and attacked it as if it was dangerous for the body). Eventually, he had to go back on dialysis and was in need of another kidney.

After a lengthy hospital stay following the operation, Mr. Slayman was finally discharged, deeming the procedure successful at that point. Doctors stated that he was no longer in need of dialysis and up to that point there had been no signs of his body rejecting the kidney.

Unfortunately, Mr. Slayman died two months later. The Massachusetts transplant team confirmed that there was ‘no indication’ of this being a result of the pig-kidney transplant.

Mr Slayman received the kidney as part of a Federal Drug Association (FDA) Expanded Access Protocol, which allows for patients to be given trial treatments or procedures if it is felt that without it their life is severely threatened. This does not mean the procedure has been approved for widespread use, rather that doctors were given permission to attempt it on Mr. Slayman, knowing the possible risks associated.

The FDA is still looking into whether this procedure could be viable on a larger scale.

Prior to the operation, it was necessary for the pig kidney to be genetically engineered, to reduce the possibility of transmission of disease and to increase the likelihood that Mr Slayman’s body would accept the organ.

There were three main parts to this, which consisted of: removing genes that the human immune system might react to; the addition of new genes that can encourage compatibility with the human body; and the deactivation of all viruses that had the potential to be transmitted.

Using genome editing technology, researchers targeted genes in the pig kidney that had a risk of transmitting diseases to Mr Slayman.

Ethical and financial concerns

Although this procedure shows spectacular progress and promises to open a new range of treatments for patients in the future, critics have commented on ethical concerns. When a new medical procedure or treatment is proposed, proponents must consider a multitude of ethical issues.

One of these includes the prospect of clinical trials. Before these transplants can be considered applicable for all patients, a wide range of trials must be conducted to ensure safety and efficacy.

Clinical trials can last around 10–15 years before a drug/procedure is finally approved. Before the clinical trial phase, it must first go through the entire research process, which includes development and testing on animals to ensure safety levels for humans.

Research found that a monkey given a gene-edited pig kidney lived for two years longer than its original prognosis – an important result for the beginning of this treatment in humans. The problem lies in the use of live participants, as a large number are needed in total across all stages. Because the long-term, or even short-term, effects of such transplants remain unknown, it is unlikely that many will be willing to take part. Moreover, it is even less likely that there will be wide range approval for these trials due to the severe risk of side effects.

Another issue lies in the protection of the human species, as such transplants raise the risk of spreading disease from the animal in which the organ is derived from. Although the organ will be genetically modified to prevent this, the risk remains because the long-term effects are unknown.

Also, additional diseases might come to the surface, meaning that scientists are unable to fully inactivate the entirety of possible viruses that could spread to humans. Not only could such diseases infect the individual transplant patient, they could spread to the surrounding population as well, creating a larger problem.

Learn more:

Critics also bring up the uncertainty of the financial aspects of of xenotransplantation. If there were to be a rise in such operations, what would happen to companies that currently provide hospitals with organs for transplants? They could go entirely out of business, switch to xenotransplantation, or simply begin to lose money.

Furthermore, were these transplants to rise in popularity, the actual cost of producing these organs is not entirely known either, especially due to the extensive genetic modifications required.

Although these are valid criticisms of xenotransplantation, it is still important to recognise the significance of the Massachusetts pig-kidney transplant. It marks the opening of new doors in organ transplantation, giving hope to reducing waiting lists.

It is truly exciting to see the new opportunities this procedure brings to the world of medicine.