18-year-old Elias Malmqvist travelled to the Arctic Circle to see how the Sámi are holding their ground

Elias feeding reindeer at Nutti Sámi Siida, a Sámi museum in Jukkasjärvi.

Picture by: OXSFJ

Article link copied.

August 1, 2025

‘Stolen land’: What Sweden’s ‘green transition’ is costing the Sámi people

Their home. Their land. Their peace.

Stolen.

Stolen by trucks and excavators digging up the earth.

For over a century, their land has been exploited by mining companies extracting iron ore and other minerals from the mountains. I am referring to the Sámi people, the Indigenous population living in the north of Sweden.

I spent a week in the Swedish part of Sápmi, the Sámi homeland, visiting communities and learning more about the people, their culture and the problems they face. As well as Sweden, the original Sápmi stretches across northern Norway, Finland and Russia.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

As soon as I stepped out of Kiruna Airport, the northernmost airport in Sweden, I noticed the construction sites, the dust and the machines, an incongruous sight among the striking green nature and clear blue skies.

From my encounters with local Sámi people, I discovered that their biggest problem is the conflict over land use. The land they believe is rightfully theirs is being exploited, against their will, to extract minerals. Sweden is now the leading exporter of iron ore in Europe and the eighth largest in the world (as of 2024).

The conflict between the Sámi and the Swedish government has been an issue for more than 100 years and is seemingly getting worse.

Mining in the region

The small town of Kiruna, located 145 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle in Swedish Lapland, is known for the Kiruna Mine, owned by the Swedish state mining company, Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB (LKAB). Opened in 1989, it is the largest iron ore mine in Europe.

Valuable minerals,including Europe’s largest-known deposit of rare earth minerals used in green technologies, have also been discovered there. Mining activity has caused tremors and land subsidence, including a significant earthquake in May 2020, which has prompted the relocationof the town, approximately three kilometres to the east, to prevent it from sinking into the ground. The relocation, currently under way, is due to be completed by 2035.

“People want the LKAB mine to survive,” Sanna Inga Poromaa, a Left Party politician in Kiruna, told Harbingers’ Magazine. “They depend on it – whether they work for the mine directly or in a supporting role.”

But the LKAB mine is not the only mine affecting Kiruna.

A new graphite mine, operated by the Australian battery materials and technology company Talga, is planned for the Vittangi area, around 75 kilometres from Kiruna, between the Torne and Vittangi rivers. In 2024, the Swedish Mining Inspectorate granted Talga a 25-year licence, with the possibility of an extension.

This mine has triggered a backlash. “For the first time in Swedish history, the state is saying: ‘You have to have this mine. You can’t say no,’” said Sanna Inga Poromaa.

Outside Kiruna, in Jokkmokk, which is considered the capital of Sámi culture in Sweden, another long-running project – the Kallak (Gállok) mine – targets one of the country’s largest untapped deposits of iron ore.

These mines are tied to Sweden’s green transition, which is aiming for net-zero emissions by 2045.

But they come at a cost: the loss of Sámi land, rights and traditions.

Elias in Jokkmokk, which is seen as the capital of Sámi culture in Sweden.

Picture by: OXSFJ OXSFJ

Henrik Blind, the mayor of Jokkmokk, told me that from the government’s perspective, “land use is about economic value – mining, timber, wind farms.”

“But from the Sámi perspective, our connection to the land is cultural, spiritual and historical. It’s about reindeer herding, yes, but also storytelling, knowledge and identity. These two views don’t fit together.”

He believes that what is being sacrificed today are Sámi culture and traditions, as the Swedish government has shown little understanding or willingness to accommodate the Sámi way of life.

Elisabeth Qvarnström, a Left Party politician based in Piteå, explains that the Vittangi mining project is presented as essential for the green transition. “However, it risks reproducing environmental injustice and violating indigenous rights,” she said.

Sanna Inga Poromaa also elaborated on the consequences of the Vittangi project: “It will ruin the reindeer herding and destroy really big areas of forest and water. That’s a really big issue here.”

The Swedish government has not yet responded to Harbingers’ questions regarding Sámi land rights and the ongoing mining projects.

Henrik Blind, mayor of Jokkmokk.

Picture by: OXSFJ

Unratified rights

One major source of frustration among Sámi leaders is Sweden’s refusal to ratify the International Labour Organisation’s ILO 169, an international convention recognising Indigenous land rights and self-determination. Only 24 countries have ratified it, including Norway (1990) and Denmark (1996). Sweden has not.

“If Sweden signed the convention,” explains Elisabeth Qvarnström, “the government would be obligated to consult Sámi communities and respect their voice in decision-making.”

This reluctance reflects a broader imbalance in power between the Sámi Parliament, a representative body elected by Sámi people in Sweden, and the Swedish government.

Qvarnström notes that while the Sámi Parliament plays an important symbolic and advisory role, it has no legislative power and is financially dependent on the state. “This reduces its ability to act forcefully on behalf of Indigenous communities,” she said.

Construction in Kiruna. [Swipe right for more]

Picture by: OXSFJ

Elias (left) meets Left Party politician Sanna Inga Poromaa.

Picture by: OXSFJ

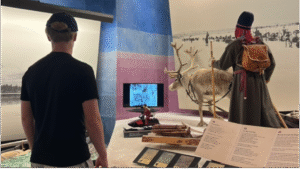

Elias at the Ájtte Museum in Jokkmokk.

Picture by: OXSFJ

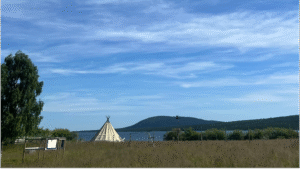

Sapmi, the Sámi homeland.

Picture by: OXSFJ

Culture at risk

In my interviews across Kiruna and Jokkmokk, Sámi community members consistently pointed out that mining doesn’t only take land, it also disrupts reindeer migration routes and threatens ecosystems central to Sámi life.

This connection was further reinforced by my visit to Ájtte Museum in Jokkmokk and Nutti Sámi Siida, a Sami museum in Jukkasjärvi, a Sami settlement where I learned how closely Sámi culture, livelihoods and identity are tied to the land and its seasonal rhythms.

While reindeer herding is not the full extent of Sámi culture, it is a main component of their lifestyle and traditions. Without access to uninterrupted land, continuing this tradition becomes increasingly difficult.

As mining projects expand across Sápmi, the future of Sámi culture, language and land-based traditions hangs in the balance, caught between national interests and Indigenous survival.

Indigenous communities around the world are facing similar struggles, as governments pursue economic or political goals at the expense of those living on valuable land. Their rights, cultures and voices deserve recognition, not removal.

No more stealing.

No more trucks and excavators.

Bring back the peace.

Written by:

Writer

Bali, Indonesia

Born in 2007 in Malmo, Elias has studied in Sweden, Chile, California, North Carolina, and Bali. He is interested in business, entrepreneurship, management and international relations and plans to study along those lines. For Harbingers’ Magazine, he writes about economics, society, international relations, and sports.

In his free time, Elias plays football, does Maui Thai, goes to the gym, enjoys riding motorbikes and spending quality time with friends and family. He has played high level football his entire life and runs a microbusiness teaching football to young athletes.

Elias speaks English and Swedish.

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism